HomeAuthor

IranMedTour Admin, Author at IRANMEDTOUR

Killer T-Cell Discovery Could Mean ‘Universal’ Cancer Treatment

A new type of killer T-cell could serve as “one-size-fits-all” cancer therapy.

Researchers at Cardiff University in Wales discovered a different kind of T-cell receptor (TCR)—one that recognizes and kills most human cancer cells while ignoring healthy ones.

The early-stage findings, published this week in the journal Nature Immunology, have not yet been tested in patients. But the team said they have “enormous potential.”

Understanding T-Cells

T-cells are a type of lymphocyte (white blood cell) that develop in the thymus gland (hence the name). Born from stem cells in bone marrow, they help protect the body from infection.

But T-cells can’t always differentiate between destructive and nourishing cells, allowing some cancerous cells to fall through the cracks.

Scientists are working to improve this system through various immunotherapies, including CAR-T—a specialized treatment that targets only a few types of cancer and has not been successful for solid tumors.

New TCR on the Block

Conventional T-cells scan other cells looking for anomalies; the system recognizes small parts of cellular proteins bound to surface-level molecules called human leukocyte antigen (HLA).

Annoyingly, HLA varies between individuals, preventing scientists from creating a single T-cell-based treatment to target most cancers.

Enter Cardiff’s unique TCR—able to recognize a range of cancers via the single HLA-like molecule MR1.

Show and Tell

Early experiments show the new, as-yet-unnamed TCR can kill lung, skin, blood, colon, breast, bone, prostate, ovarian, kidney, and cervical cancer cells. A germ of all trades, if you will.

Lead study author Andrew Sewell, an expert in T-cells from Cardiff University, said it is “highly unusual” to find a TCR with such broad cancer specificity, raising the prospect of “universal” therapy.

“Current TCR-based therapies can only be used in a minority of patients with a minority of cancers,” he explained. “We hope this new TCR may provide us with a different route to target and destroy a wide range of cancers in all individuals.”

When injected into cancerous mice bearing a human immune system, the MR1-spotting T-cells showed “encouraging” cancer-clearing results.

The team also showed that modified T-cells of melanoma patients destroyed not only their cancer cells but those of other patients’ in the lab, regardless of HLA type.

“Cancer-targeting via MR1-restricted T-cells is an exciting new frontier,” Sewell said. “Previously nobody believed this could be possible.”

What’s next? Experiments are underway to determine exactly how the new TCR distinguishes between healthy cells and cancer. Researchers suspect it may involve changes in cellular metabolism.

The Cardiff group hopes to trial their new approach in patients later this year, following further safety testing.

“There are plenty of hurdles to overcome,” Sewell admitted. “However, if this testing is successful, then I would hope this new treatment could be in use in patients in a few years.”

A Renewable Source of Cancer-Fighting T-Cells

Last year, UCLA researchers developed a technique for turning pluripotent stem cells (capable of giving rise to every cell type in the body) into cancer-killing T-cells.

The approach uses artificial thymic organoids to mimic the thymus and produce T-cells without needing to collect them from already-depleted patients.

And, when combined with gene editing, it could allow scientists to generate a virtually unlimited supply of T-cells for large-scale treatment.

How does this new TCR work?

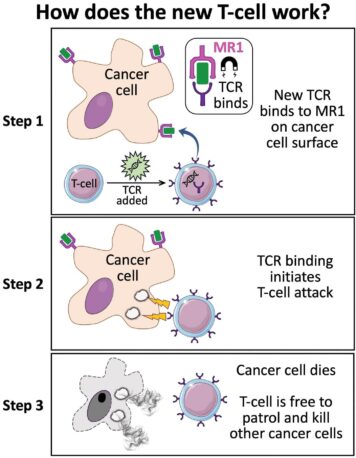

Conventional T-cells scan the surface of other cells to find anomalies and eliminate cancerous cells – which express abnormal proteins – but ignore cells that contain only “normal” proteins.

The scanning system recognizes small parts of cellular proteins that are bound to cell-surface molecules called human leukocyte antigen (HLA), allowing killer T-cells to see what’s occurring inside cells by scanning their surface.

HLA varies widely between individuals, which has previously prevented scientists from creating a single T-cell-based treatment that targets most cancers in all people.

But the Cardiff study, published today in Nature Immunology, describes a unique TCR that can recognize many types of cancer via a single HLA-like molecule called MR1.

Unlike HLA, MR1 does not vary in the human population – meaning it is a hugely attractive new target for immunotherapies.